“What do you call a consumer who wants to buy everything you have, doesn’t care what it costs and is less than five feet tall? A marketer’s dream? Nope. You call them kids.”

AdRelevance Intelligence Report, 2000

While marketing to children is nothing new – having first been introduced in the 1960s – the aggressive marketing to those on the cusp of adolescence (ages 9-14) is a phenomenon that has arisen much more recently, in direct synchronicity with the “internet age” and the rise of new media (1990s-present). This demographic, the so-called “tween” group (for “in between”), was in fact entirely developed by and for marketers, and took on economic significance before it took on cultural significance (1). It would not be a hyperbolism to suggest that tween culture was, in fact, entirely manufactured by the marketing machine. To understand the aggressive and pervasive nature of tween marketing, it’s important to first understand why this arbitrary distinction was created. Why “tweens”? What tweens have to offer to marketers that is so important vs. what children and teenagers already provide as consumers? Why has this market exploded the way it has in the last decade? The answer boils down to the fact that tweens, being in a transitory period, face a great degree of sudden vulnerability. And, at the same time, they retain full access to parental funds. This juxtaposition of susceptibility to influence and spending power is more prevalent among tweens than it is among teens or children.

Tweens’ Influence on Household Spending

Tweens are too young to legally earn their own money in order to attain what they want, so retain a child’s relatively unquestioned reliance on (and thus access to) their parent’s funds. According to BusinessWeek magazine, “Of the reported US$ 51 billion spent by tweens themselves, an additional $170 billion was spent by parents and family members directly for them” in the United States annually (2). In the UK, we have 11 million people aged 15 and under, with a remarkable total expenditure of £12 billion from children up to 18, money often coming from own pocket money (alas parent’s pockets!) and part-time jobs (2b). This does not merely represent an access to more money on the part of tweens, but also a far greater lack of discretion about what they will spend it on. Teens, by contrast, who have begun to earn and control their own funds, have more awareness of the fact that money is finite and needs to be prioritized around what they really want, introducing a level of agency and choosiness about what they buy which is the precursor to adult spending habits. At the same time, tweens have just enough independence to exert power over household spending decisions owing to a shift in family dynamics which took place during the 1990s, and is known to play a key role in modern marketing strategy.(3) This shift saw a large number of tweens living in households where both parents work and in single-parent households (in 1994, one in four households in the United States with children was headed by a single parent, up from one in eight in 1970 [Miller, 1994]), and led to far more responsibility being placed upon tweens and teens (e.g. grocery shopping duties, which fully one-third of tweens have), giving them greater purchasing power and more independence. (Cuneo, 1989; McLaughlin, 1991; Miller, 1994; Rickard, 1994)(3) Tweens have been shown to have more “discretionary purchasing power than younger children or older adolescents, to shop at least three times a week, and to save 30% of their spending money for higher ticket items.” (McLaughlin, 1991) This access and right to adult funds and influence over what is done with them combined with tweens’ unique psychological vulnerabilities make them extremely appealing to marketers, and has been a strong factor in the developing pervasiveness of marketing directed at them.

The Role of Peer Pressure in Marketing to Tweens

As mentioned earlier, tweens are in a unique phase of psychosocial vulnerability. Most children in this age group are going through a fundamental change in their place in the social hierarchy around them, moving from schools where they were the oldest, most respected, “coolest” kids, to environments that are new, alien, and place them as the youngest and most vulnerable members. They have to “start over” socially at exactly the same time as their own bodies are developing in sudden, often troubling ways. The tween years are a period of intense change: mental, physical, emotional, and social. This breeds an incredibly intense pressure to “fit in”. Most surveys conducted on the priorities of tweens note fitting in on the top of, or very near the top of, the list. Naturally, this creates a deep need to have what their peers have and look how their peers look — a marketer’s haven for creating trends around brands. Teens, by contrast, are increasingly rebellious and eager to carve out individual identities, meaning that mainstream pop culture (and therefore the marketing therein) is something many teens grow to define themselves against, rather than by, an obvious challenge to marketers (for whom mainstream appeal is the goal, as it brings with it maximum profit potential). The pop idols and Disney shows that were the height of cool when they were twelve are the epitome of “lame” by 15 or 16 — hence why many pop stars (e.g. Justin Bieber, Miley Cyrus) are aggressively marketed to smitten tweens while often being almost universally loathed by older teens. Research confirms the fact that tweens place even more emphasis on brand names than do older adolescents (Cuneo, 1989; Fitzgerald, 1992; Koester May, 1985; McLaughlin, 1991; Simpson, 1994). They are particularly concerned with having the “cool” brands when it comes to clothing and other matters of appearance. They much more strongly associate conformity with the need for acceptance, approval, and harmonious relationships with others (Batra, Kahle, Rose, Shoham, 1994).(3) Today’s tweens are also the most “wired” generation in history (heavily using the internet and mobile devices), meaning this peer pressure travels with them everywhere they go, and thus so does the potential to market to it. Tweens are also far more likely to click on things like banner ads than other age groups and are more susceptible to viral marketing tactics that promote the spread of a message from one user to another. Marketing to tweens via interactive social venues like chat rooms, forums, and e-mail have been noted to be especially effective.(4) Due to this, the prevalence of online marketing (both obvious and subtly worked into interactive media) has risen sharply over the last decade.

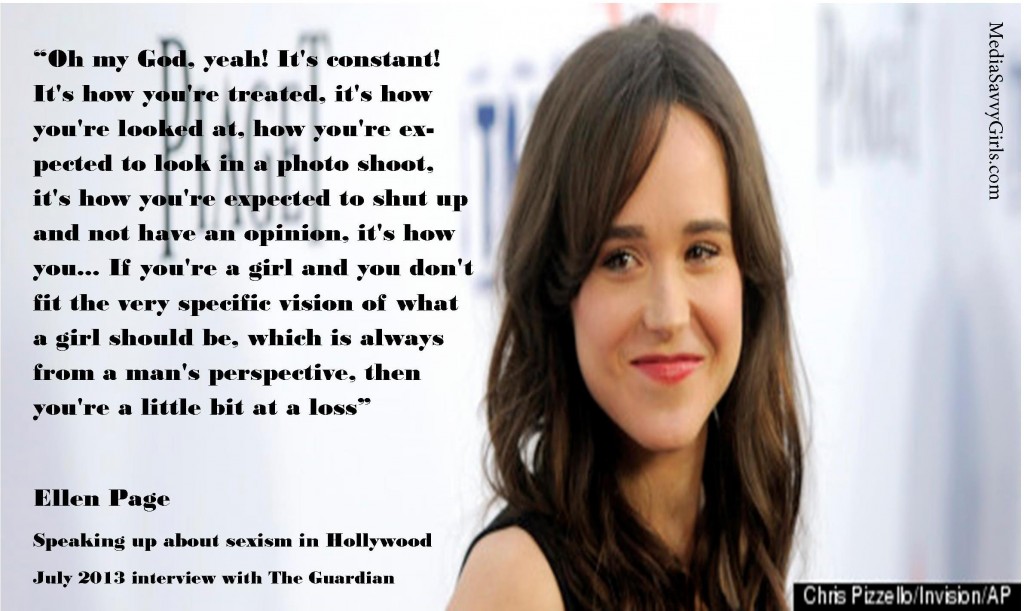

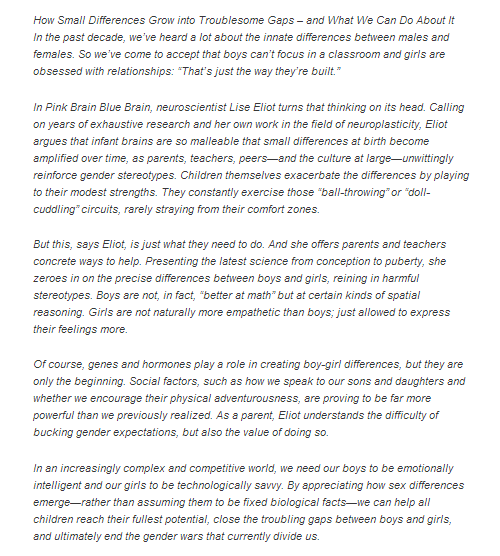

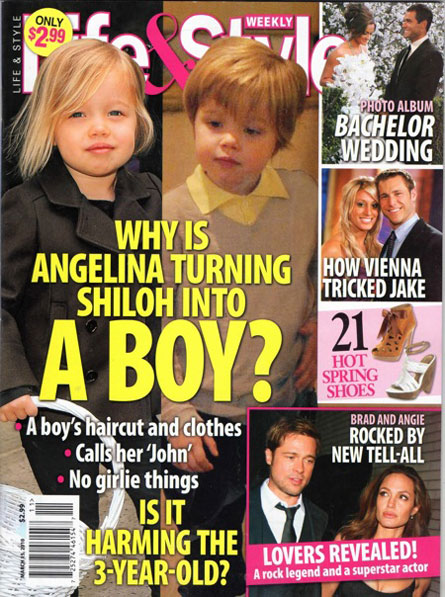

The Impact of Puberty: Body Image and Gender Roles

No discussion of tweens could be complete without examining the role of puberty; the rapid changes taking place in tweens’ bodies throws how these young people relate to one another into chaos, thrusting gender roles into sudden and stark relief and raising big questions about sex, dating, marriage, and the possibility of having children. Little girls and boys who were simply playmates a year or two prior suddenly find they have to redefine their peer roles around their emerging sexuality. This creates a deep need in tweens to understand themselves as gendered persons, and tween marketing capitalizes on this by offering strongly gendered media that plays into tweens’ heightened body awareness and subsequent concerns about their appearance. While this newfound awareness is hard on the self-esteem of both genders, it has been found to be significantly harder on girls (owing in large part to an intense perceived pressure to be thin), with research conducted throughout the United States, Korea, and Australia showing that the body dissatisfaction which arises in girls during puberty “is associated with lower levels of self-esteem and increased likelihood of depression among early adolescent girls.” (Newman & Newman, 2006, p. 303.) The earlier a girl physically matures, the worse this impact tends to be, and the more likely serious consequences (such as eating disorders) become.(5) As self esteem is a “central component of personality and identity” and is centrally tied to one’s “confidence in one’s ability to think and to cope with the challenges of life and confidence in one’s right to be happy” (Clancy and Dollinger, 1993)(6), young girls’ desire to identify with themselves in a positive way (and thereby achieve greater agency and success) makes the consumption of images of beautiful, thin young women incredibly appealing—something tween television programming and advertising media taps into (and profits from) frequently. To assess this phenomenon, Ashton Lee Gerding, a humanities student, and Nancy Signorielli, professor of communication at the University of Delaware, analysed 49 episodes of 40 distinct American tween television programs that aired in 2011 on Disney Channel, Disney XD, Nickelodeon and the Turner Cartoon Network. They catalogued and examined more than 200 characters in terms of their attractiveness, gender-related behaviour and personality characteristics such as bravery or ability to handle technology (7): “Tween viewers are undergoing an important developmental stage and actively seek cues about gender,” said Gerding. “Television programming can play an important role in that development, so we examined tween television programming. Overall, girls were portrayed as more attractive, more concerned about their appearance, and received more comments about their appearance than male characters. However, female and male characters were equally likely to be handy with technology and exhibit bravery. This sends the message that girls and boys can participate in and do the same things, but that girls should be attractive and work to maintain this attractiveness”. “Tween television programs may help to shape the way kids think about the roles that are available for them. Therefore, we advise parents to watch these programs with their kids and talk with their tweens about their roles in society. We also advocate for media literacy programs that could mitigate some of the potential negative effects of these programs.”

Tips for Parents: How to Moderate the Impact of Tween Marketing

Marketing is an inevitable part of the world most of us live in, so parents cannot hope to entirely shield their tweens from the impact of marketing on their developing adolescence. Parents can, however, give their tweens tools to help them cope with the barrage, and parents should never undervalue their role in this area. No matter how pervasive the media and marketing have become, tweens still cite their parents as their biggest influence when it comes to important decisions, even in “private” areas like sexuality. Parents can, absolutely, make a strong difference in how teens interpret and deal with the media and the marketing that is so aggressively aimed toward them. Prof. Agnes Nairn and Ed Mayo with the help of UK charity Care for the Family completed a “pester power” online survey and published a pamphlet Pester-power: Families surviving the Consumer Society (2007) which include a comprehensive summary of “survival tips” adopted by parents against the current marketing pressure. The booklet can be downloaded from this link: http://goo.gl/Q34ME9 (10). In this blogpost I want to include some suggestions provided by the Media Awareness Network, the Canadian Paediatric Society, and Susan Linn (psychologist and author of Consuming Kids: The Hostile Takeover of Childhood)(8), which should help parents navigate the murky waters of children commercialisation:

- Start young. Children are influenced by marketing from a very young age.

- Limit children’s exposure to advertising on television and on the Internet. Don’t allow them to have televisions or Internet-enabled computers in their rooms, and limit TV time to one or two hours per day.

- Talk to your kids about how advertising works and what advertisers are trying to accomplish. Explain that advertising is a multi-billion dollar business whose goal is to get people to buy things, and that they are very good at it.

- Encourage kids to think critically about marketing messages. You can start as small as you like: last year a Grade 6 math class in Thunder Bay, Ontario debunked a “fun fact” on a package of Smarties, which claimed that Canadians eat enough Smarties each year to circle the earth 350 times. They found that in order for the claim to be true, either the earth would have to be a lot smaller, or each Smartie would have to be 3.5 metres in diameter.

- Help kids to understand the strategies used by advertisers. Talk with kids about specific ads: “How do you feel about the people in the ad? Do you want to be like them? Why or why not? Does the ad make you feel uncool for not owning the product, or that you’ll feel good about yourself if you buy the product? What are some other ways you could get those feelings, without buying the product? Has the ad used any ambiguous words or impressive-sounding facts and figures to make the product sound better than it is? At the end, did the announcer say anything like ‘some assembly required’ or ‘batteries not included’?”

- Explain about product placement: if characters in a movie or TV show are using a particular brand, the advertiser probably paid a lot of money for it to be there.

- Discuss how your kids can be smart, responsible consumers by knowing what is good for them and what is not, what is good for the environment and what is not, and what is good value for money.

- Educate children about nutrition using your country’s Food Guide. Discuss whether eating only things you see on TV makes for a healthy, balanced diet. Make a distinction between “everyday” foods and “sometimes” foods.

- Before going grocery shopping, decide exactly what you plan to buy, including snacks and treats. Having a list that you and your kids have discussed ahead of time makes it easier to avoid impulse purchases and set limits in the store.

- Monitor your own media habits and buying habits, and change them if necessary. Children pick up early on what is important to their parents.

- Most importantly, make sure TV, Internet, and video games “screen time” is well balanced with family time, active/creative play, playing outdoors, reading, and other activities without marketing attached!

Main references: 1. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file?accession=bgsu1119390228&disposition=inline 2. http://www.businessweek.com/stories/2005-10-11/marketing-and-tweens2b. www.tgisurveys.com/tgi/Youth2006.PDF and Youthscape Report: Attitudes, Behaviour and Spending Habits of UK Kids & Teens, Q4: 2013 https://www.marketresearch.com/Swapit-v3893/Youthscape-Attitudes-Behaviour-Spending-Habits-8261648/ 3. http://42051.faithweb.com/Tween%20consumes%20catalog%20clothing%20purchase%20behavior.html 4. http://www.cdc.gov/youthcampaign/research/PDF/LitReview.pdf 5. http://www.brighthubeducation.com/teaching-methods-tips/3320-development-in-early-adolescence-puberty-and-low-self-esteem/ 6. http://www.drwrite.com/research/sample2.shtml 7.http://www.science20.com/news_articles/tween_programming_is_disney_promoting_stereotypes_or_creating_what_kids_want_to_watch-134661 8. http://www.aboutkidshealth.ca/en/news/newsandfeatures/pages/target-market-children-as-consumers.aspx 9. http://www.slideshare.net/gerdavandamme/whitepaper-digital-marketing-to-generation-spongebob 10. http://www.careforthefamily.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/301-08-ppinf02-pester-power-booklet-10-september-2008.pdf