YouTube, like many of the social media services we rely on, was born mostly out of necessity: back in 2005, two former Paypal employees—Chad Hurley and Steve Chen—realised they had no way of sharing the video they had just shot at a conference. Video files were too large to email and uploading them to the web was incredibly tedious, so the natural solution was to create an efficient online media sharing site.[1] However, despite these pragmatic beginnings, it took just a few years (and a 1.6 billion dollar Google buyout) for YouTube to begin profoundly altering the way we consume media, prompting average viewers to move beyond passive observation and tackle the task of content creation. As increasingly sophisticated smartphones armed those viewers with better and better cameras, a revolution was born—and nowhere has it been felt more profoundly than within the teen demographic. Today, more and more young people are naming vloggers (video bloggers) when asked who their favourite celebrities are: According to a 2014 survey commissioned by Variety magazine, the five most influential stars among 13-18 year-olds are all YouTube sensations, with the comedy duo Smosh taking the lead.[2]

For parents, the idea of their children looking up to these (often apparently wholesome) vloggers rather than an endless succession of morally questionable, highly sexualised, and obviously-manufactured mainstream ‘stars’ often produces a profound sense of relief. However, the vlogger phenomenon is not above warranting a critical appraisal; though you won’t find many of these young ‘cyber celebrities’ glorifying drug abuse or stripping naked on album covers, their status as role models—particularly role models for young women—remains somewhat questionable.

Meet The Vloggers: Who Are They?

In addition to Smosh (Ian Andrew Hecox and Anthony Padilla, famous for their off-beat brand of charming, zany improvised comedy) some of the vloggers most popular with teens include:

- Felix Arvid Ulf Kjellberg (PewDiePie): A handsome young Swedish gamer, PewDiePie has accrued a staggering 30 million+ subscribers thanks to his humorous real-time commentary on video games. Though PewDiePie refers to his fans as his ‘bros’, research suggests that he appeals to both teen girls and boys in fairly equal measure. Though some parents may take issue with his use of strong language, he’s generally perceived as good-natured and even charitable, being a major supporter of the charity ‘Save the Children’.

- Ryan Higa (NigaHiga): Ryan’s unique ability to master both satirical humour and topical rants (which he refers to as ‘off the pill’ rants as he engages in them while off his ADHD medication) has drawn over 12 million subscribers to his channel. Like many successful YouTubers, Ryan also has a penchant for genuine personal confession that endears him to his young fans; he has even opened up about his struggles as a victim of bullying.

- Bethany Mota (formerly Macbarbie07): Bethany largely owes her subscriber base of over 7 million to the invention of ‘haul’ videos, wherein she reveals her purchases to her fans after shopping sprees. She also gives fashion and beauty advice. Mota, who won a 2014 Teen Choice Award, usually broadcasts from her archetypal feminine bedroom, which is adorned with colorful accessories, such as strings of pink hearts.

- Tyler Oakley: YouTube’s most famous member of the LGBTQ community, ‘out and proud’ vlogger Tyler Oakley has amassed over 5 million fans and won two Teen Choice Awards. In addition to being a spokesman for LGBTQ rights, Oakley is much-loved for his inspirational videos and special guest features.

- Zoe Sugg (Zoella): Another style and beauty vlogger, Zoella’s effervescent personality, comprehensive reviews of beauty products, and hair and makeup tutorials have netted her over 5 million fans, primarily young girls. Zoella’s genuinely clean image appeals to parents and advertisers alike while her openness about her struggles with anxiety make her relatable to many young people.

- Tanya Burr: Like Zoella, Tanya—a former make-up counter girl—has amassed millions of followers while dispensing beauty advice to young girls. So successful is Burr that she now has her own lipstick and nail-polish range in Superdrug and she is often pursued by ‘high fashion’ brands (e.g. Chanel, Dior and YSL), all of whom send her freebies with the hope that they will get featured in Burr’s ‘Get Ready With Me’ make-up tutorials. Tanya, whole also maintains a clean and ‘down to earth’ image, also occasionally makes baking videos.

Deconstructing The Message: How Do Vloggers Stack Up As Role Models?

The 2000s have thus far been disappointing where conventional celebrity role models are concerned: from the shameless excesses of the Hiltons at the beginning of the millennium, to the self-destruction and/or sexualisation of female Disney stars intended for the preteen market (Lindsay Lohan, Miley Cyrus, et al), the practised vapidity of the Kardashians or the frank obnoxiousness of many teen heart-throb (Justin Bieber, notoriously), we’ve been given solid reasons to look beyond traditional media for inspiration. But how are vloggers—the elected leaders of the YouTube generation—really holding up against their old media counterparts?

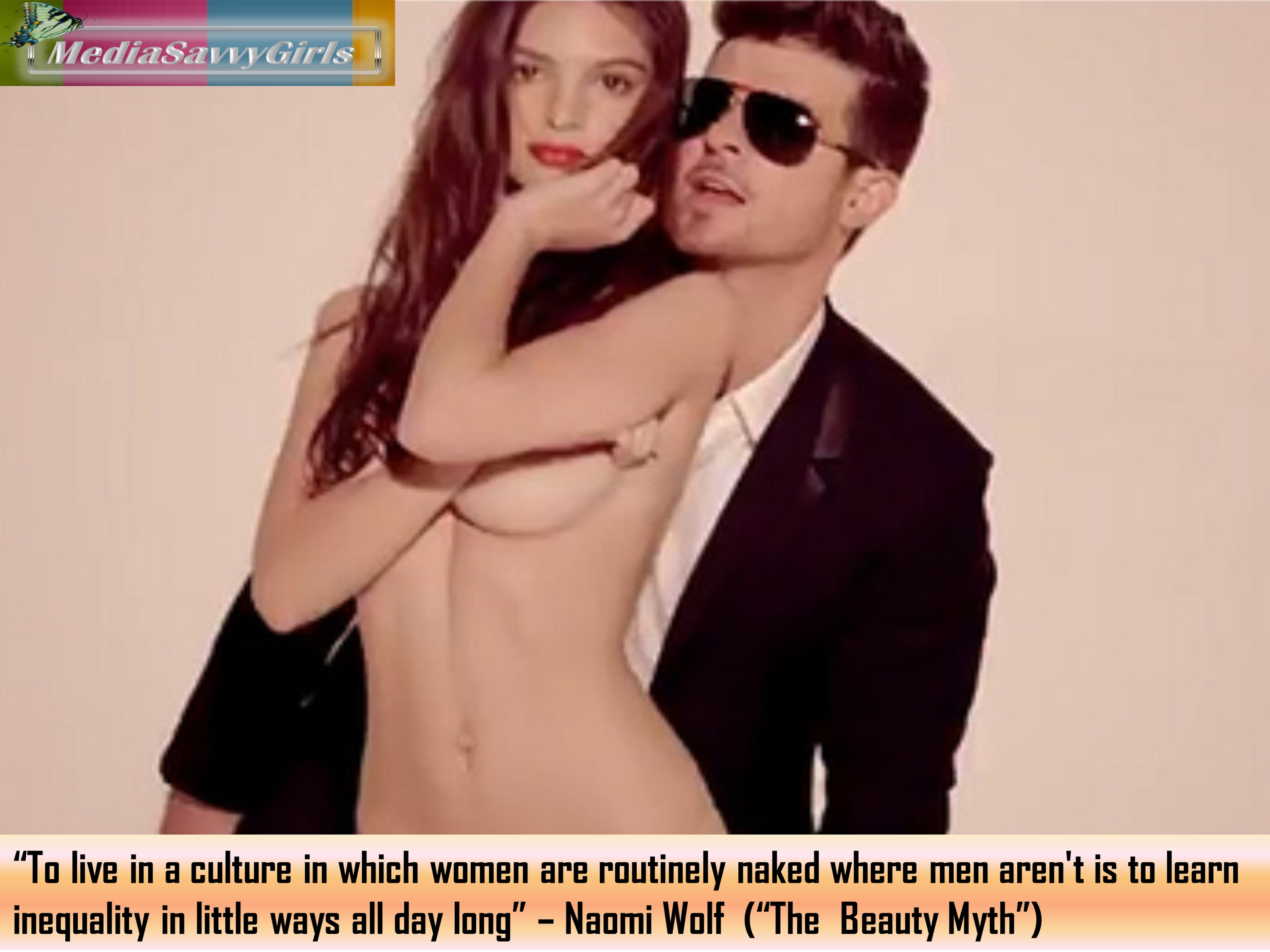

There’s little doubt that many ‘cyber celebrities’ are at least more genuine than their Hollywood brethren; operating without handlers and the direct oversight of big business, they have worked hard to create both their own images and their own content. However, while this is assuredly admirable, popular vloggers are more often a reflection of the ‘status quo’ than they are radically reshaping it. The mere fact that almost all of the top vloggers intended for young girls run shopping, fashion, and beauty vlogs[1] alone (while popular male vloggers cover niches that range from gaming to comedy to commentary and more) is cause for thoughtful consideration.

Beauty bloggers like Zoella have also been criticised for their all-too-familiar hypocrisy: Preaching a message of self-acceptance and spouting ‘you’re good enough as you are’ rhetoric while directing their young fans toward the purchase of a sizable collection of beauty products. Conspicuous consumption, too, appears here to stay; not only are some vlogger celebrities, like Bethany Mota, famous almost entirely for shopping, Tanya Burr openly encourages her young fans to purchase brands far out of their price range. When questioned if the products she promotes aren’t too expensive for her teen fans, Burr flippantly shot back, ‘No, they can save up, or they can request them from their parents as birthday presents.’[1] Meanwhile, brilliant young women like Shirley Eniang—a maths student with dreams of becoming a pilot or an aeronautical engineer—content themselves with talking almost exclusively about different ways of wearing skinny jeans and styling ‘cute milkmaid braids for spring’.

Certainly, there’s nothing inherently wrong with wanting to look good, but the lack of diversity in female-intended content remains a troubling phenomenon among celebrity vloggers, particularly when paired with aggressive advertising and a decidedly mixed message where self-love is concerned. This peculiar brand of hypocrisy seems to have changed but little since the days of women’s magazines.

There are, however, signs of hope. The prevalence of LGBTQ cyber celebrities certainly surpasses that which is found in the mainstream media, indicating a fairer and more even playing field for young people of all identities and orientations. Likewise, not only do many vloggers (including fashion and beauty vloggers) speak up about charitable causes and attempt to shed light on real issues that affect young people (e.g. Zoella’s frank discussion of her issues with anxiety), some popular YouTube channels (run by women and largely for women) feature honest and helpful discussion about women’s health issues and sexuality. Laci Green, for example (a sex education activist from the San Francisco Bay Area) is doing her part to compensate for the lack of adequate sex ed in the United States with her popular YouTube show, Sex+. Meanwhile, vloggers like Dianna Cowan (Physics Girl) are finding entertaining and informative ways to get young women interested in historically male-dominated fields like maths and science. Evidently, the potential for change is here—we just need to decide what to do with it.

Vloggers As Role Models: Helping Your Child Choose

When it comes to embracing vloggers as role models, parents and young people alike should draw on their power to freely elect—with views, ‘likes’, and subscriptions—their own icons within the digital sphere. Parents should stay informed about current vlogging sensations and (as when dealing with traditional celebrities) attempt to guide, but not control, their children’s’ choices. Likewise, it’s always a good idea to teach young people to think critically about their favourites, to ask themselves why they are drawn to a given celebrity, what he or she is really saying, and what he or she hopes to achieve by broadcasting his or her message.

With due scrutiny, it’s possible that the ‘YouTube revolution’ will help to resurrect and refresh the tarnished concept of media-based mentors thanks to its potential for greater authenticity, the inherent relatability of its stars, and the complete creative freedom it grants to its young visionaries. After all, the best role model isn’t someone who is perfect; it’s someone who genuinely and honestly embraces his or her imperfections and then uses them as part of a platform for enhancing the common good.

References:

[1] The revolution wasn’t televised: The early days of YouTube, Todd Wasserman. http://mashable.com/2015/02/14/youtube-history/#EPsBG7ZgVsqS

[2] Survey: YouTube Stars More Popular Than Mainstream Celebs Among U.S. Teens, Susanne Ault. http://variety.com/2014/digital/news/survey-youtube-stars-more-popular-than-mainstream-celebs-among-u-s-teens-1201275245/

[3] 11 Most Subscribed Youtube Girls Channels, http://richclubgirl.com/rich-photos/11-most-subscribed-youtube-girls-channels/

[4] Meet the YouTube big hitters: The bright young vloggers who have more fans than 1D, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/you/article-2656209/The-teen-phenomenon-thats-taking-Youtube.html

25 Vloggers Under 25 Who Are Owning The World Of YouTube, http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2014/12/17/25-vloggers-under-25-who-are-owning-the-world-of-youtube_n_6340280.html

Why Youtubers Aren’t The Worst Teen Role Models Ever, http://www.mookychick.co.uk/opinion/love-and-life/youtubers-teenage-role-models.php

Zoella isn’t the perfect role model girls think she is, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/11259853/Zoella-isnt-the-perfect-role-model-teen-girls-think-she-is.html

YouTube UK: 20 of Britain’s most popular online video bloggers https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/apr/07/youtube-uk-20-online-video-bloggers