We are constantly surrounded by symbols of beauty – gorgeous tanned women in bikini on the billboards, mysterious smoky-eyed seductresses, mothers that manage to take care of career, household and children, while still looking like goddesses. Female beauty is, as we’ve been taught, something essential. A woman needs to look her best at all times. But it turns out that “her best” is quite a slippery term…

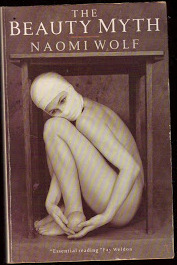

“The Beauty Myth”, published in 1991, is one land-marking book focusing on how the beauty idea influences women’s life. With power come responsibilities, the book says, and these responsibilities – at least for women – mean adhering to certain standards. The “iron maiden”, as Naomi Wolf refers to it, is the impossible standard that punishes women both physically and psychologically for their inability to achieve it.

The ideal of female beauty isn’t new. It has started as early as the ancient times, with the ancient Egyptians using kohl to blacken their lashes and upper lids, and Romans darkening their eyes with burnt matches and fading their freckles with young boys’ urine. In history, beauty has always been a symbol of power and social status. The wealthy Renaissance women had to pluck their hair lines in order to make their foreheads seem higher, and to bleach their hairs to make them blonder. This trend continued up to the 1990s, where the ideal for female beauty was Kate Moss, the symbol of extreme thinness, with a strung-out and emaciated appearance, both in face and body.

We’ve all heard about the Photoshop debates and the unrealistic beauty standards, but this is just the tip of the iceberg. Think about how many magazines publish dietary and exercise tips that guarantee you to “lose weight quickly”. How many tabloids compete to be the first to “comment on” (“shaming” is probably a better word) a celebrity’s weight gain. It’s not surprising that the incidence of eating disorders have doubled in the last 15 years.

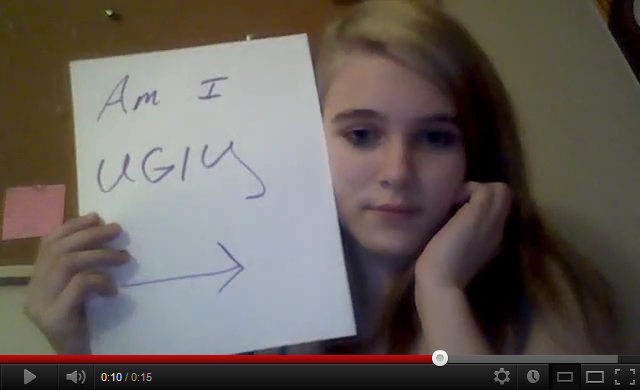

The problem is not surrounding women with unreal physical standards. The issue is that women believe they’re expected to look like this, because they can. This is how the horrific cycle of self-loathing begins. Every time you open a magazine, you’re urged to lose weight quickly, to dye your hair, to shave your body, to be as feminine as possible. You can’t be beautiful if you have pores or gray hairs. You have wrinkles or freckles? Then you better do something about it. The problem is intensified by the pervasiveness of todays’ media: it’s very difficult to escape all these images, slogans and messages as they are ubiquitous and thus become the very fabric of our constant preoccupation with the way we look. Young girls’ role models are YouTubers like Zoella, whose videos are all about teaching girls how to achieve “that perfect look” through hours of make-up.

So many more girls today suffer from eating disorders, anxiety, depression, self-harm/cutting and trichotillomania. The more girls self-objectify, the more likely is that they will suffer from these issues. The worst problem is that we believe we need to be beautiful in order to be happy, successful and loved. We always fear that all our other qualities – no matter how great – won’t be enough to make us feel worthy in the eyes of others; unless we achieve the standard of beauty which we deem acceptable, we feel that we are falling short, while in reality whom we compete against are only abstract ideals. We will run and starve to death, or binge and purge, to get thinner, but they’ll always be a next magazine cover with a thinner or fairer model. I’ve personally practiced 15 years of this struggle before I started considering that perhaps my perspective was flawed…

The “beauty ideal” has influenced women’s throughout history, regardless of the country or culture. The beauty standards may change according to country-based preferences (although there is evidence that the white/western type of beauty is increasingly held as a standard more globally; an example is offered by some Asian countries – see this article about South Korea – where the western beauty ideal has prompted an alarming growth in the number of girls resorting to cosmetic surgery to “fix” their Asian features. South Koreans currently have more plastic surgery than in any other country according to 2013 figures, with the craze particularly popular among 19 to 49-year-olds), but still these beauty standards dictate our life and judge who can be happy and who needs to “work more” in order to achieve their dreams.

In a world in which other skills and qualities in a girl are – should we say? – “less regularly” emphasized, beauty has become synonymous with happiness and girls are constantly pushed towards it, and punished if they fail to conform. The question is how can we revert the brainwashing once done and “unlearn” the bits of a beauty-obsessed culture that doesn’t serve us well, while keeping the ones that make us feel empowered. If only we could teach girls (and boys too) that there is nothing inherently wrong in the appreciation of feminine beauty or the grooming practices in themselves, but that, rather, the problems start when we take as imperative what society/media/advertisers tell us in regard to what our beauty ideal should be (particularly if that ideal of beauty become narrower, unrealistic and applied universally) and when we fail to strike a balance with all the other dimensions of our life, self and world, so that our preoccupation with appearance gradually becomes an obsession.

I know that for me and many other women, awareness has only come with age. I am still convinced in the power of awareness and participation, but I wonder what type of experiences can permanently raise young girls’ consciousness of being beauty-bound? And would that consciousness – once raised – be able to eradicate the feeling of unworthiness many young girls are battling with? Or is this – like many seem to contend – just a process that necessarily most girls will need to go through, living it and experiencing it in their own skin before finding themselves “liberated” only at a later stage of maturity?